The Housing Crisis

The UK is facing a severe housing crisis that has far-reaching impacts on its society and economy. Over the past few decades, the housing supply per capita has flatlined and gone into reverse in the last few years as our population grows, yet housing development has not kept pace, leading to an acute shortage of homes. This shortage affects the broader economy as costs increase, reducing disposable income and limiting labour mobility. Moreover, it can even impact fertility rates (which in the last 10 years have hit crisis level) as young families delay or don’t have children due to insecurity and economic concerns.

To meet the Labour Party’s ambitious target of building 1.5 million new homes over the next five years, we need more than strategic reforms—we need bold, transformative actions. By addressing key challenges in the housing sector, we can incentivise housebuilding while minimising the necessary trade-offs.

In the spirit of boldness, I give you my 5 prescriptions and their challenges:

1. Streamline Approval Processes

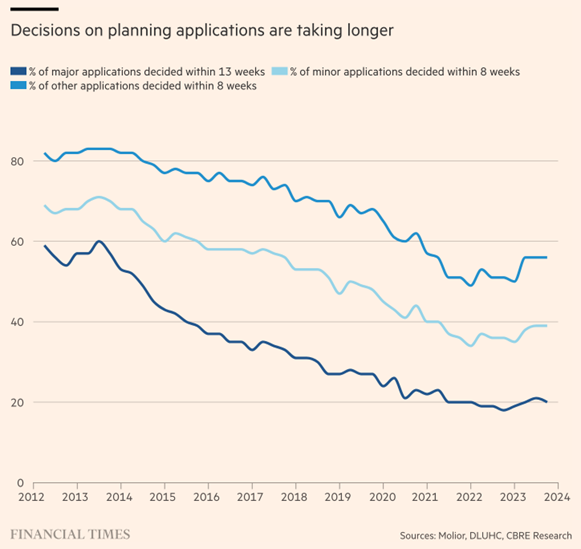

Problem: The approval process for housing development is now notoriously slow and cumbersome, causing significant delays in project commencement and completion.

Solution: A radical change would be to introduce automatic approvals for projects that meet predefined criteria, such as affordable housing quotas, sustainability standards, and community benefits. This approach can significantly cut down on delays and bureaucratic red tape.

Evidence: Empirical evidence from Germany shows that German “Bebauungsplan” (development plan) system allows for faster approvals when projects align with pre-established criteria [1].

Trade-offs: While this will accelerate development, it may reduce local authorities’ ability to scrutinise individual projects, suboptimal outcomes can be minimised by having unambiguous and strict criteria.

Graph showing how planning applications are taking longer, sourced from the FT – How Labour will try to unlock Britain’s planning system.

2. Enhance Community Benefits

Problem: Community opposition is a major hurdle in new developments, often leading to project delays or cancellations.

Solution: Establish community land trusts (CLTs) where local communities have a stake in the land for housing. Additionally, require developers to contribute a percentage of profits to local amenities and services, fostering goodwill and reducing opposition.

Evidence: In the United States, the Champlain Housing Trust in Vermont has successfully provided affordable housing while ensuring community control [3]. In Germany, the Mietshäuser Syndikat has created a network of community-owned housing projects [4].

Trade-offs: While this approach can reduce opposition, it may also reduce the overall profitability of projects, potentially deterring some developers or investors. Proceed with caution.

3. Simplify Planning Obligations

Problem: Planning obligations, or Section 106 agreements, often delay projects due to complex negotiations and tit-for-tat engagements.

Solution: Simplify these obligations through standardised templates and fixed contribution rates. Additionally, implement a “use-it-or-lose-it” policy for planning permissions to ensure that developers act swiftly, avoiding land banking and speculative delays.

Evidence: The Netherlands has implemented a streamlined system of developer contributions that has helped accelerate housing delivery [5].

Trade-offs: Standardised obligations may not adequately address the unique needs of each community, potentially leading to a one-size-fits-all approach, however, if carefully designed and eligible for review in 12 month windows then the best of both worlds can be achieved.

4. Integrated Infrasturcture Planning

Problem: Lack of coordinated infrastructure development often hampers housing projects and reduces their overall quality and sustainability.

Solution: Establish a national infrastructure fund dedicated to supporting housing projects. This fund could be financed through a mix of public and private investments and managed by a dedicated infrastructure agency tasked with ensuring timely and coordinated development of transport, schools, and healthcare facilities alongside housing.

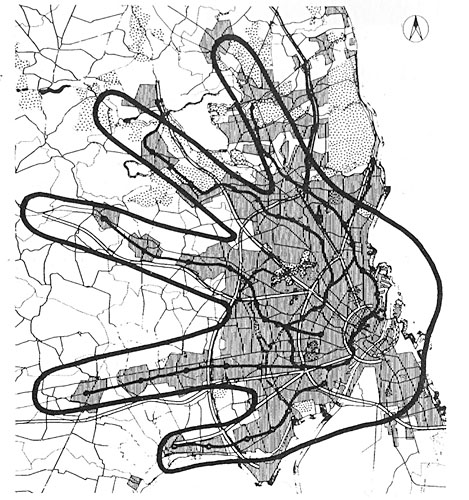

Evidence: Sweden’s “Stockholm model” of integrated infrastructure and housing development has been highly successful in creating sustainable urban areas [6]. Denmark’s “Five Finger Plan” for Copenhagen also demonstrates the benefits of integrated planning [7].

Trade-offs: This approach requires significant upfront public investment and coordination between multiple agencies, which can be challenging to implement, but certainly less challenging that some of Labour’s other goals, and with a 174 majority, Labour is only limited by its own competence.

In 1947, Copenhagen established the Five Finger Plan to build designated corridors of urban development.

5. Support for Small Developers

Problem: Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often struggle with the complexities of the planning system and the ever-increasing costs associated with obtaining planning permission have left housebuilding a big player’s game.

Solution: Create a national small developer support programme, providing financial assistance, reduced fees, and technical support to SMEs.

Evidence: The Dutch Housing Factory supports modular housing construction by small developers, increasing their capacity to contribute to housing supply [8].

Trade-offs: Focusing resources on smaller developers may reduce the overall efficiency of housing delivery, as larger developers often benefit from economies of scale.

Addressing Capacity and Control Concerns

Despite these promising strategies, the UK faces significant challenges in mobilising the necessary capacity to achieve these ambitious housing targets, as it requires an additional 250,000 workers by 2028. The construction industry is facing a severe skills shortage, and the government’s control over the pace and quality of development is limited due to the dominance of private developers.

To address the capacity issue, it is essential to invest heavily in training and apprenticeships in the construction sector. The government should collaborate with industry to develop alluring and comprehensive training programmes that equip workers with the necessary skills. Attracting foreign skilled labour through streamlined visa processes may be needed in crucial trades and disciplines which can temporarily alleviate the shortage while domestic capacity is built up.

Incentivising Private Developers

Given that private developers are the primary drivers of housebuilding, not government, aligning their incentives with public goals is crucial. The government can offer tax incentives, grants, and subsidies for projects that meet specific criteria, such as affordable housing and sustainability targets, and penalties and taxes for those which land bank and delay development. Singapore’s housing development model, which involves a mix of public and private initiatives, has been successful in delivering high-quality, affordable housing at scale [10]. In the current political climate, incentives for private developers may be seen as an inappropriate use of public funds so a cost neutral mechanism of incentives may be the best approach here.

Balancing Trade-Offs

Achieving these ambitious housing goals will require difficult trade-offs. Rigorous focus on local biodiversity, species protection, and other sustainability and affordable homes requirements can affect the viability and speed of building projects. To meet the targets, some of these regulations may need to be relaxed.

For instance, adopting a more flexible approach to environmental regulations in designated high-need areas can expedite development without sacrificing long-term sustainability goals. Similarly, streamlining the affordable housing requirements in initial phases of large projects can help break ground faster.

An ambitious sustainability plan for a new UEL campus.

Japan’s flexible zoning laws have contributed to higher housing production and more affordable housing prices compared to other developed countries [11], lessons can be learned. Deregulation sounds frightening to half of the political spectrum, which fears environmental degradation and reduced housing quality, however, we must remember regulation is about quality not quantity, and the chronic shortage of housing and ongoing use of sub-standard properties comes with its own social and environmental costs.

Policy makers would be wise to remember there are no answers, just trade-offs.

References

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, Germany (2019). “Land Use Planning and Building Permission in Germany.”

- Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, Netherlands. (2020). “National Policy Strategy for Infrastructure and Spatial Planning.”

- Davis, J. E. (2010). “The Community Land Trust Reader.” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

- Mietshäuser Syndikat. (2021). “Annual Report 2020.

- OECD. (2017). “The Governance of Land Use in OECD Countries: Policy Analysis and Recommendations.”

- City of Stockholm. (2018). “The Stockholm Model: Urban Development and Planning.”

- Danish Ministry of the Environment. (2015). “The Finger Plan: A Strategy for the Development of the Greater Copenhagen Area.”

- Dutch Housing Factory. (2021). “Innovation in Modular Housing Construction.”

- Australian Government Department of Home Affairs. (2021). “Skilled Migration Program Report.”

- Housing and Development Board, Singapore. (2020). “Annual Report 2019/2020.”

- Harding, R. (2016). “Why Tokyo is the land of rising home construction but not prices.” Financial Times.

Chris Hocknell, Director

Chris brings over 17 years’ experience of supporting the built environment and corporate world with their sustainability goals. Specialising in sustainability strategy development, Chris works closely with clients to assess and understand their carbon and environmental footprint.