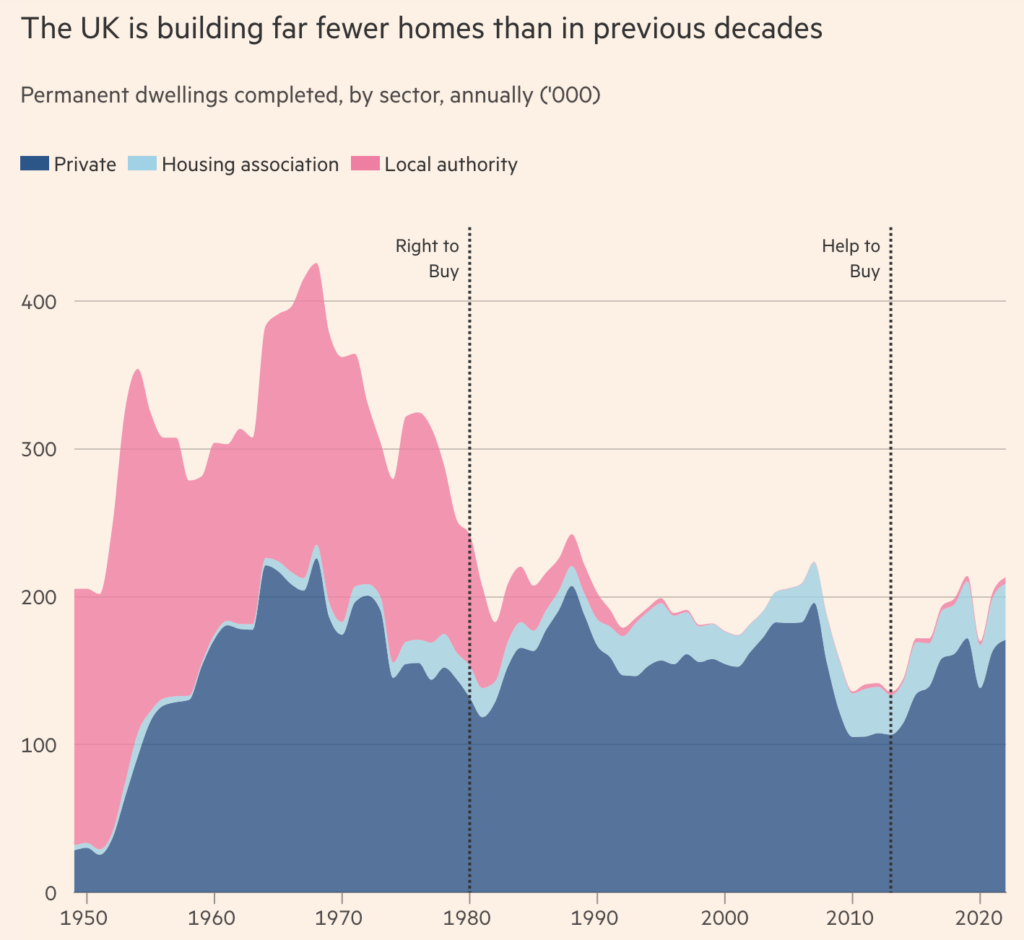

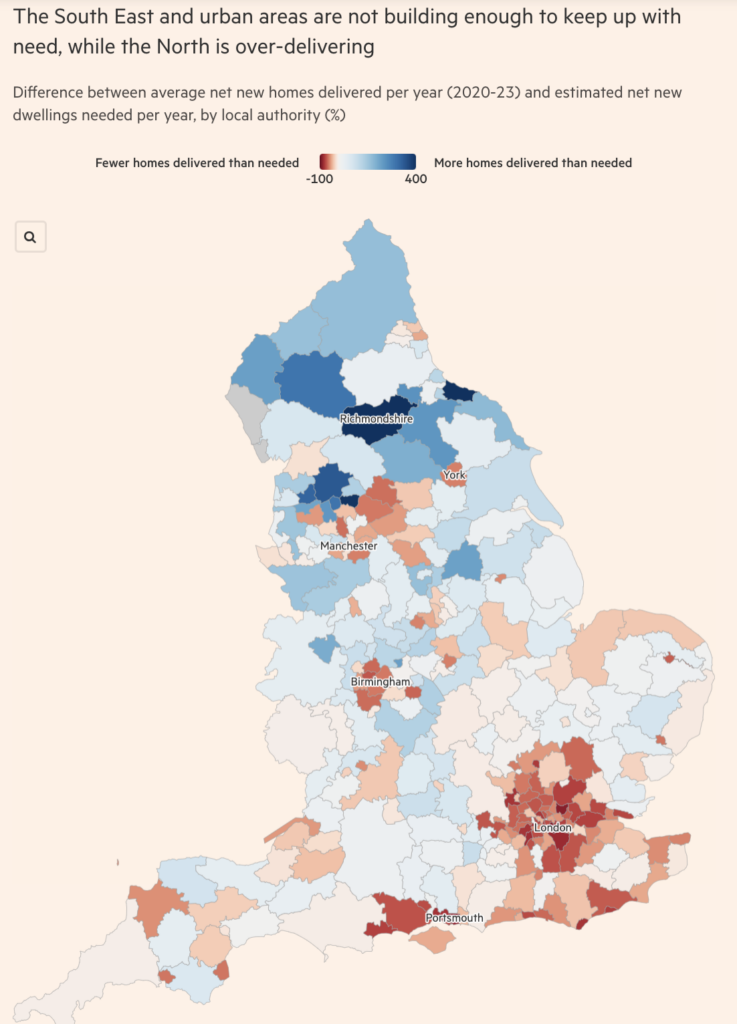

The Housing Challenge

The UK is currently meeting only half of its housing supply targets. A series of articles published by the Financial Times in recent months (1, 2 and 3) finds that we are falling behind our peer countries such as France, Germany and even Japan and the gap is widening. While factors such as National Grid capacity and Nimby-ism (‘Not in my backyard’) are slowing down the delivery of new homes, research found that the chronic undersupply of housing was more deeply rooted in its “complex and unpredictable planning system”. They state that:

“Its highly discretionary system places an unreasonably high burden of proof on projects to satisfy a mass of stakeholders and regulations before they can proceed.”

Often it is not just the red tape that delays the process, but also the myriad of requirements that need to be met at planning.

FT analysis of the UK housing challenge

Large developments require around 79 supporting documents for approval, and these include technical reports that meet compliance requirements across multiple, often competing factors. In just the last few years, the introduction of Building Regulation Part L 2021 followed by the Future Homes Standard, Building Regulations Part O, the BRE’s revised guidance on daylight and sunlight analysis and the recently published RICS Whole Life Cycle Assessment guidance have collectively introduced stringent performance requirements which are necessary to push the built environment space towards UK’s Net Zero goal.

It is however, the responsibility of design teams as well as local authorities to interpret and apply these variables to achieve the best and most appropriate outcomes. This collaboration, or battle (depending on where you stand), often results in a better building, but comes at a substantial cost in time and resources. If we are serious about building the 4 million homes that we are currently short of, and to stop subjecting generations to ever increasing living expenses we will need a smarter approach to compliance.

The Planning Approval Dilemma

We recently contributed to a planning application for a single large, detached dwelling in a central London locality and were pleasantly surprised to be working with a team and a client that prioritised sustainability. Going beyond compliance, the proposal adopted a truly circular approach and targeted a LETI Band A+ rating as well as passive strategies such as an underground thermal energy store to reduce demand and increased battery capacity for solar energy to reduce peak energy demand.

While the council’s response was appreciative of the exemplary performance this development targeted, they wanted more information on why the fabric performance could not be pushed further and the scheme was unable to meet future weather compliance for overheating.

In this case we found that pushing fabric performance further to meet the compliance requirement would have a negative impact on overheating and the whole life carbon of the building.

Our argument was ‘is it worth targeting an incremental improvement in the fabric at the cost of these other factors when overall the development can demonstrate a reduction in emissions by 70% over the baseline?’ At Eight Versa we explore design options by using an approach called parametric design, which essentially means using building simulation tools to evaluate the performance of multiple specifications so that we can identify the optimal design solution. For a deep dive into how we used parametric design to arrive at the optimum design strategy you can read our parametric design excerpt here.

Piecing the Puzzle Together

There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to a compliant design. Compliance needs to be looked at with a sense of practicality and feasibility. Consultants and especially planners need to recognise there are diminishing returns in every action we undertake; if you keep pushing the performance of a design parameter you will soon find that the marginal increase of the next push gets so low that the benefit is less than your margin of error. Moreover, pushing something up another notch often results in trade-offs elsewhere, which when added together results in a less favourable overall outcome.

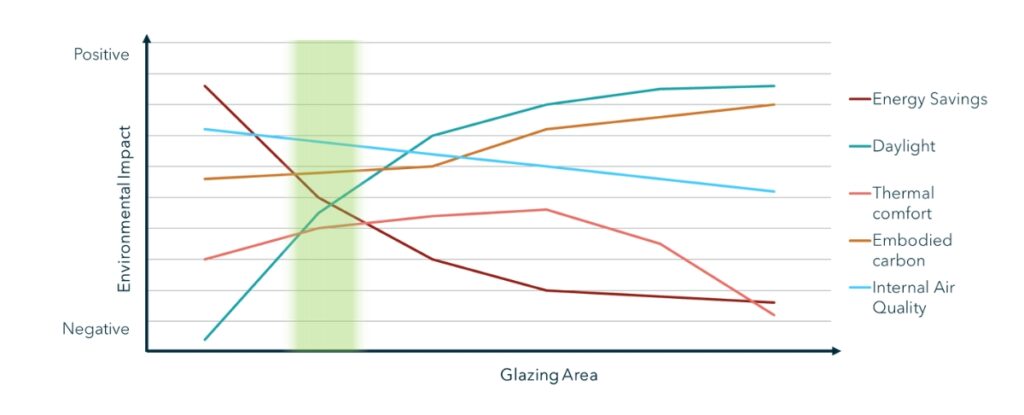

An illustrative example of how trade-offs commonly manifest for a single variable such as glazing area is shown below.

The optimum point is in the green shaded band, but there are a reasonable range of outcomes here. In this taxing application we utilised parametric design like the illustration above to enable a decision to be arrived at quicker.

We understand that a stringent planning system is necessary to achieve a high-quality built environment. However, we are increasingly experiencing obsessive litigation of smaller compliance requirements, which tends to lead to tunnel vision, and we often miss the bigger picture. It is worth noting that some humility is also needed here, as most of our models have an accuracy range of +/-20%, at best, and we have a huge performance gap, so arguing over decimal points in a theoretical compliance model is often wasted resources.

A better approach is needed. Parametric studies should be used more frequently as a practical way to provide the big picture for stakeholders to ensure a quick and decisive design can be made. Designers and consultants should be doing this anyway in their design process, so we can think of this as a more systematic and tidied up way of ‘showing your workings’. On the other side of the coin, we need decision makers and authorities to engage with this approach, recognising that obsessing over minutiae in modelled performance won’t make much of an impact on climate change, but will make an impact on planning application costs and incentives to build.

To meet the current and growing demand for housing and infrastructure and the ever-increasing compliance requirements we will need a more sophisticated approach to design evaluation as well as a goal-oriented approach to key stages such as planning and design. Otherwise, there will be an inevitable compromise in either our development aspirations or sustainability goals.

Rishika Shroff, Building Performance Manager

Rishika is a Building Performance Manager with an architectural background that enables her to work with design teams and create solutions that can enhance performance while maintaining coherence with their creative ideology.

Jenny Thomollari, Sustainability and Building Performance Consultant

Jenny is a Sustainability and Building Performance Consultant in the Building Performance Analysis and Strategy team. She has experience working in the fields of design and construction with different engineering teams for various residential and non-residential projects.

If you’d like sustainability support with your building project. Feel free to book a meeting with one of our team to discuss further.