Head in the Sand

Did you know Europe is the fastest-warming continent in the world? According to EEA’s Climate Risk Assessment data, extreme heat is becoming more frequent, downpours and other precipitation extremes are increasing, and we’ve seen enough floods in recent years to know the cost and devastation of such events.

Economic losses from coastal floods alone could exceed EUR 1 trillion per year. Long term, these risks can be abated by fast and effective reductions in greenhouse gas emissions across the board. However, even with swift decarbonisation action, the unavoidable impacts of climate change will still happen. Yet by and large the built environment seems to have its head in the sand.

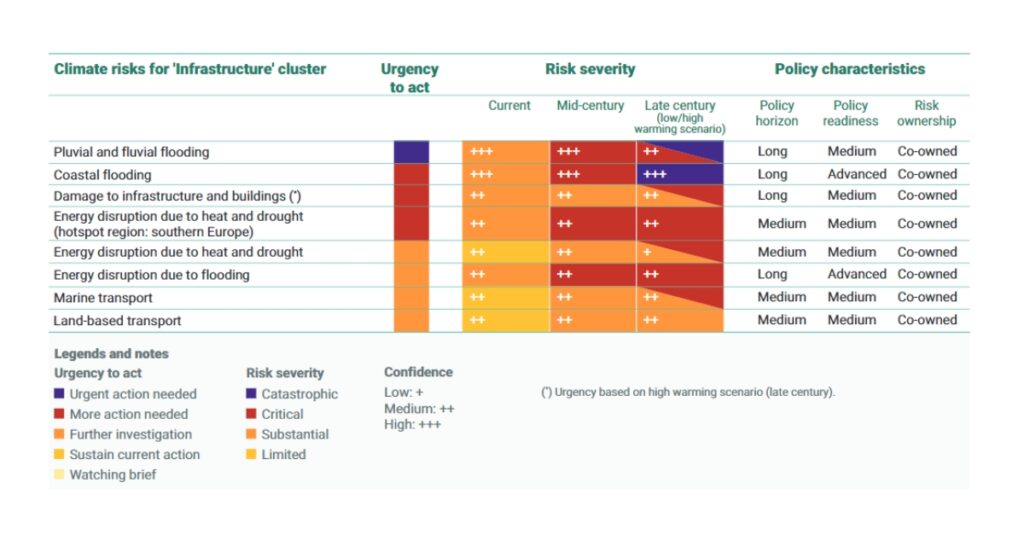

The hazards that come from the increasing number and severity of natural events can undermine the stability of any asset and portfolio value. The EEA’s Climate Risk Assessment highlights the urgency to act and the risk severity of each climate risk on our infrastructure (Table 1). While the UK is relatively in a less vulnerable position than other countries, it still has a lot to contend with in a changing climate. Moreover, European or global asset holders need to contend with managing different solutions required in every geography. We wrote about this in 2022 in our 3C’s for ESG in Real Estate whitepaper, however not a lot has changed when it comes to the developer’s mindsets.

Why is the built environment not doing enough to ensure our infrastructure is climate resilient?

Table 1 – Assessment of Major Risks from the EEA’s Climate Risks Assessment Report 2024

Slow to Action

You’ll see from Table 1 that the policy horizon is long for the majority of climate risks. This tends to lead to unpreparedness and a ‘we’ll do it tomorrow’ approach when it comes to the adaption of our building stock. Part of the problem is that the risk is perceived as either too big and nebulous – how can I predict the climate? Moreover, it is often largely considered to be someone else’s problem. The risks are co-owned and someone else may own the asset in 10 years’ time.

This is a logical position but is somewhat naive on the side of the developers. The big insurance companies while quiet and conservative, are the best in the world when it comes to risk management, and they are taking climate risk as seriously as one can. If this matter is not dealt with it will lead to stranded assets.

Stranded Assets

Stranded assets are one of the most serious consequences of failing to integrate climate resilience into your building from the beginning. An asset that may not hold its value is anathema to the investment world, a stranded asset would be a building which has suffered unanticipated devaluations or converts itself into a financial liability. Stranded assets may have been due to changes in regulation (i.e. requiring high-cost equipment upgrades), climate impacts like local flooding, and changes to the economy making their asset less preferential.

All of these factors can wreak havoc in the investment sphere as the need to shift to a lower-carbon economy changes the rules of the game. For example, the oil and gas sectors are grappling with the challenge of managing potential stranded assets amidst growing activism from the public and increased regulatory pressure to address the climate change ramifications of fossil fuel extraction. This dynamic will be felt across other industries as well. However, there are climate adaption solutions that can be applied now to avoid this happening in both the near and long term.

Building Resilience Adaption

If we look at both existing buildings and new construction we can see how they each can be adapted for greater climate resilience.

1. Existing Buildings

To enhance the resilience of an existing building against various climate change scenarios, retrofitting adaptation measures are essential. These measures aim to mitigate vulnerabilities and risks effectively. While such solutions are available, the real challenge lies in navigating the constraints and high-cost trade-offs inherent in adapting an existing building successfully. Additionally, determining the most probable climate risks that could impact your building and identifying the corresponding mitigation strategies adds another layer of complexity to the process which requires expert input.

Consider a scenario where the risk of flooding is high, which is one of the largest risks for UK assets. Before considering resilience measures within the building, you will need evaluate the site-specific flood risk (note high-level screening via publicly available maps is inadequate) and implement Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDs) in the surrounding area. SuDs should be designed to efficiently manage rainfall effectively when accounting for the most serious storm event in at least 30 years under the future climate change scenario, thus mitigating flood risks to your building for the long term.

Conversely, in areas where urban design leads to increased risks of overheating from heatwaves, implementing redesign strategies like shading systems to minimise heat gains, resizing ventilation to deal with higher air exchange demand, or upgrading the building’s glazing system to reject solar gain will be necessary. You will find this heat stress is a hyper local risk issue and requires that you know everything about your building and adjacent building topography so you can estimate the issues you’ll be dealing with. Heat stress is a technical discipline and will require expert modelling and building physics analysis, rules of thumb won’t work, so you need someone who understands how a building’s energy balance works in reality.

2. New Build Opportunities

New developments have the enormous benefit of being able to incorporate climate resilience strategies from the design stage. However, it requires a forward-thinking approach that adequately evaluates the future risks and opportunities, which is often harder than it sounds in a budget and time constrained construction project.

While innovation and resilience in buildings is continually evolving, several fundamentals must be considered for new builds. Remember that the onus and expectation is greater on new buildings as they don’t have the justification of legacy constraints unlike existing buildings:

Structures:

- Flooding: Increased precipitation and rising sea levels threaten buildings, causing foundational damage and moisture-related issues.

- Storms and Wind Damage: Enhanced storm frequency and severity may exceed buildings’ design limits, causing wind and water damage.

- Temperature Extremes: Fluctuating temperatures can cause material expansion and contraction, leading to structural wear.

- Subsidence: Prolonged dry periods can cause ground subsidence, especially in clay-rich soils, undermining foundations.

- Coastal Erosion: Rising sea levels and stronger storms accelerate erosion, risking buildings near coastlines.

- Material Deterioration: Increased humidity and moisture and UV exposure can hasten the decay of construction materials.

Architectural Design/Massing:

- Landscaping and Site Design: Well considered landscaping can offer natural cooling, wind shielding, and effective stormwater management, enhancing resilience.

- Orientation and Shape: Proper orientation reduces energy needs by maximising natural light and minimising solar heat gain, an elongated form on the east-west axis can be effective.

- Compactness: A compact shape lessens the surface area exposed to more extreme weather, improving the energy balance.

- Elevated Design: In flood-prone areas, elevating buildings or designing ground floors to allow water flow through can prevent damage.

- Roof Design: Sloped roofs enhance water runoff, green roofs manage stormwater, and reflective roofs reduce heat absorption.

- Façade Systems: Adjustable façades, overhangs, and shading devices optimise indoor climate and protect against weather elements.

- Buffer Zones: Features like sunrooms, porches, or vegetation act as climate buffers, moderating the impact of sun, wind, and rain.

- Materials: Employing materials with high thermal mass helps stabilise indoor temperatures, lessening the need for mechanical control.

Mechanical and Electrical Systems:

- Resilient HVAC: Design for extreme temperatures to maintain comfort and prevent weather-related damage.

- Waterproof Electrics: Elevate and waterproof critical electrical equipment to ensure power continuity during floods.

- Surge Protection: Install surge protectors to safeguard against electrical surges from storms.

- Backup Power: Incorporate generators or battery storage to keep essential systems running during any outages.

- Redundant Systems: Implement dual systems for key mechanical and electrical functions such as pumps provide backups in case of failure.

- Stormwater Management: Integrate rainwater management more effective drainage with climate change flow volumes to mitigate flooding risks.

- Cooling Efficiency: Optimise systems to more rapidly reduce cooling needs during the increasing summer heatwaves.

- Adaptive Lighting: Utilise adaptive lighting to minimise energy use and heat output in summer.

Starting Today

Achieving climate resilience requires translating your pledges into tangible actions. Whether its integrating resilience into existing structures or designing it into new construction, it must feature in your portfolio to enhance long term performance and to maintain or increase financial returns. It is worth bearing mind the strategic relevance of this; as the climate changes and all assets are placed under physical and financially driven stress, those who have adapted will come out ahead of the pack. Climate resilience is not just a valuable risk management mechanism, but also financial and operational opportunity. Adopting this long-term strategic perspective is necessary to appropriately manage the challenge, and if done properly enormous benefits lay ahead.

Chris Hocknell, Director

Chris brings over 18 years’ experience of supporting the built environment and corporate world with their sustainability goals. Specialising in sustainability strategy development, Chris works closely with clients to assess and understand their carbon and environmental footprint.