More than 85% of building stock in the UK was constructed before 1990s, with a significant portion of these structures falling short of the current energy performance standards. There are two contrasting solutions to this challenging situation;

1. Demolish existing buildings and construct new high performing buildings

OR

2. Retrofit the existing poor performing buildings

When considering energy efficiency, you’d be forgiven to think the most obvious option would be to start with a clean slate and demolish the building. However, it’s imperative to factor in the significant carbon emissions with demolition and reconstruction that can render this decision impractical and more costly in the long-term. Especially as the payback for low energy retrofitting measures has significantly reduced over the last few years, making refurbishment more viable than ever before.

The Segmented Approach

The current regulations on energy performance for existing properties and new builds tip the balance in favour of demolition as the energy requirements for new build are a lot higher. The introduction of Part L 2021 last year, meant that any new build would achieve a 30% reduction in carbon as compared to its predecessor Part L 2013, which is a positive step, but not that significant when compared with the very ambitious 75–80% carbon reduction which will be required by the Future Homes Standard.

On the face of this it sounds like problem solved, however new construction comprises only 1% of building stock each year, and less than 15% of the building stock we currently have was built after 1990. This means if the UK is going to achieve its 2050 Net Zero targets, deep refurbishments must be a fundamental part of that strategy.

Further Retrofitting Setbacks

Counterintuitively, the much-needed momentum towards retrofitting buildings for efficiency has been slowed by the government’s recent announcement that landlords will no longer be required to improve EPC ratings for their properties. Instead, to encourage upgrades, the Boiler Upgrade Grant scheme has been expanded to larger grants of £7,500 to help households who want to replace their gas boilers with a low-carbon alternative such as a heat pump. However, our experience on many projects that are grappling with the EPC rating improvement challenge has shown us that it is not as simple as churning out heating replacement strategies to achieve low carbon buildings.

Additionally, retrofits have some further challenges beyond carbon emissions. Persuading owners and asset manager to opt for retrofit is made more challenging because in the UK, retrofits carry a hidden financial penalty. Some improvements have been made in tax exemptions over the last year and VAT has been scrapped on certain energy-saving home improvements, such as insulation and solar panels. But, unlike new builds, retrofits are not subject to the VAT exemption on building materials and services.

The other major challenge with retrofitting is the practical execution. The property is vacated for an extensive period of time, there is always unintended damage and additional costs for making-good effected parts of the building, and additional temporary works and logistical challenges in refurbishment are costly and slow down the construction programme. For these reasons property owners and developers typically believe money is better spent on building new or developing a large extension is more favourable as a greater sale/ resale price can be achieved. This is opposed to large-scale retrofits where the return is marginal and the risks are higher.

The Power of Retrofitting

Despite these constraints retrofitting can be a more economically and environmentally viable option than demolition in many cases. Previously, we carried out an analysis on EPC in England and Wales to determine the available energy performance upgrades and the potential savings homeowners could benefit from. Due to the rise in energy prices, this research demonstrated the economic benefits from improving energy efficiency in properties to be as high as £20billion across England and Wales households alone.

This can also be true for a non-domestic development. Carrying out a ‘hot spot’ analysis of the baseline performance is core to identifying low hanging fruit. For example, we have found that with lighting retrofits and the introduction of a MVHR and heat pump system, an office building (even with heritage constraints) could jump from an EPC rating of D to A without any fabric improvements. This is notable because it runs counter to the sacred ‘fabric-first’ approach which at times is not applicable for refurbishments. Also, as the variables in the equation have changed over the last 10 years (energy and technology costs, grid decarbonisation and technological development) retrofitting with better services can provide a more cost effective outcome.

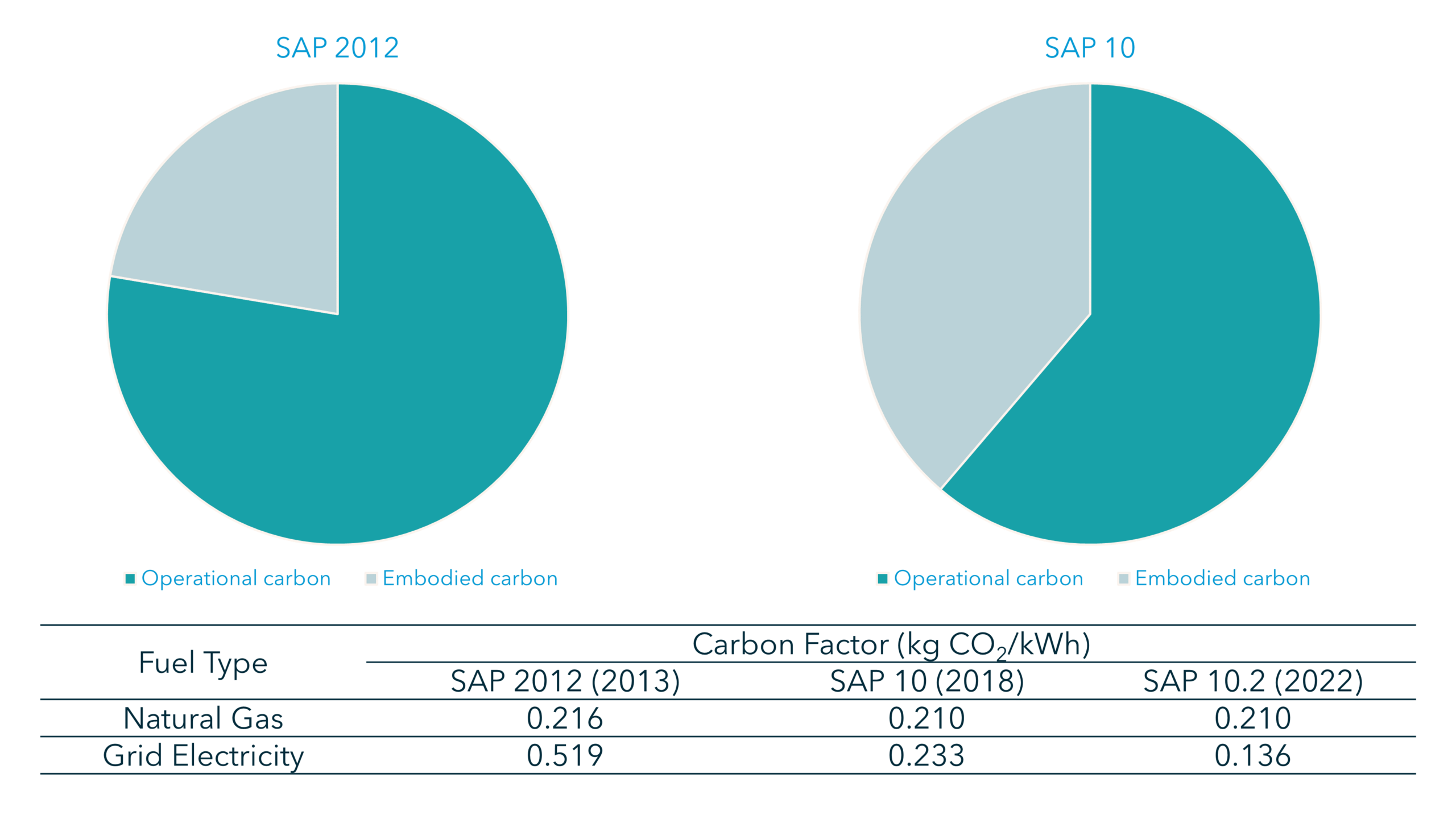

With the rapid decarbonisation of the electricity grid (between SAP 2012 and SAP 10.2 [released in 2022] the carbon factor for electricity has reduced by 75%), the operational emissions resulting from using technologies such as air source heat pumps are reducing. However, embodied carbon remains a significant influence as to which strategy to take and often can be the deciding factor when adding up the main economic and environmental wins.

Decarbonisation of the Electrical Grid

So, the question is – what is the optimal development decision that is both economically and environmentally beneficial?

The Whole Life Carbon Approach

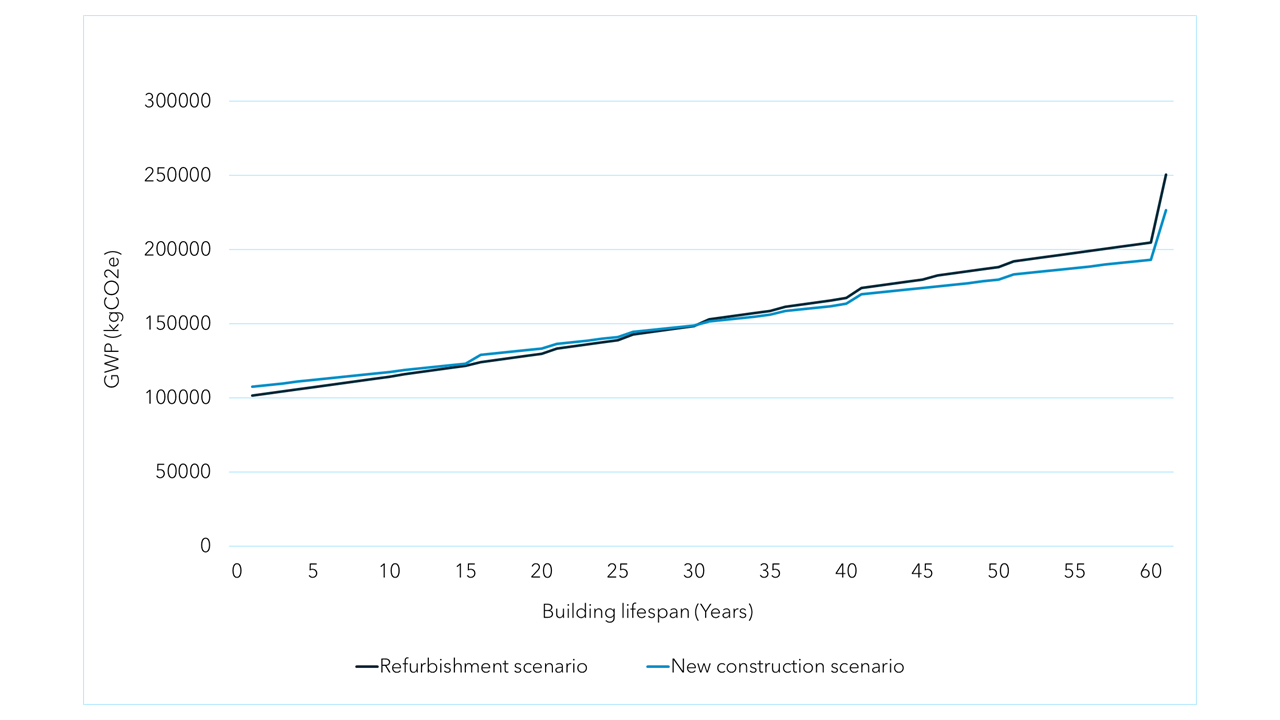

The best way to answer this question other than to say ‘it depends’ would be to complete a whole life carbon comparison study. This study offers a detailed assessment of carbon emissions throughout the building’s entire lifespan, encompassing embodied carbon from materials and operational carbon stemming from energy consumption, while also considering potential cost savings associated with recommended upgrades. This analysis also delineates the building’s carbon performance over its lifespan, pinpointing the threshold at which one of the cases surpasses the other.

In a recent study conducted by Eight Versa for a deep retrofit vs new construction case this tipping point was between 20-30 years.

Comparison Refurb vs. New Build

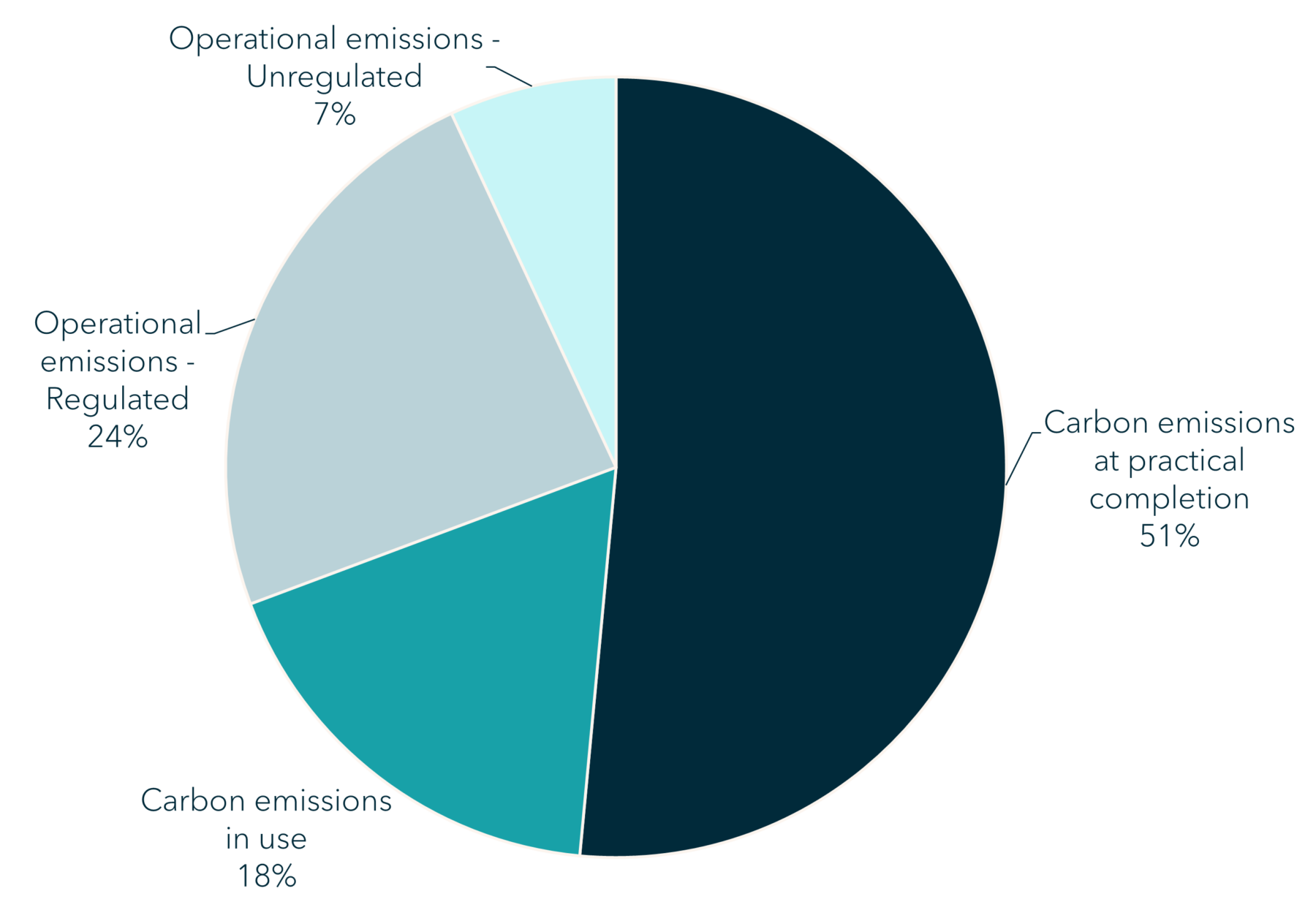

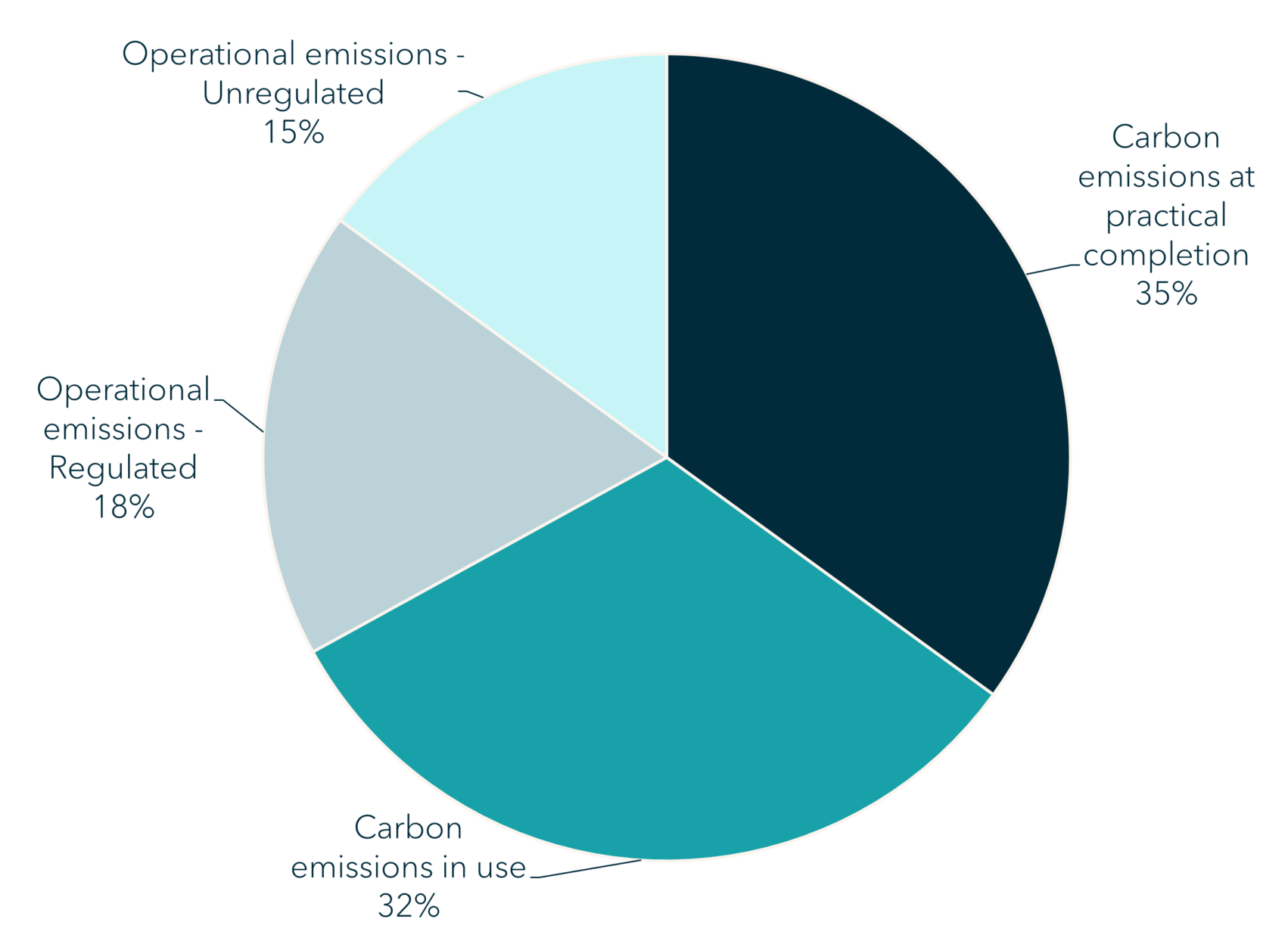

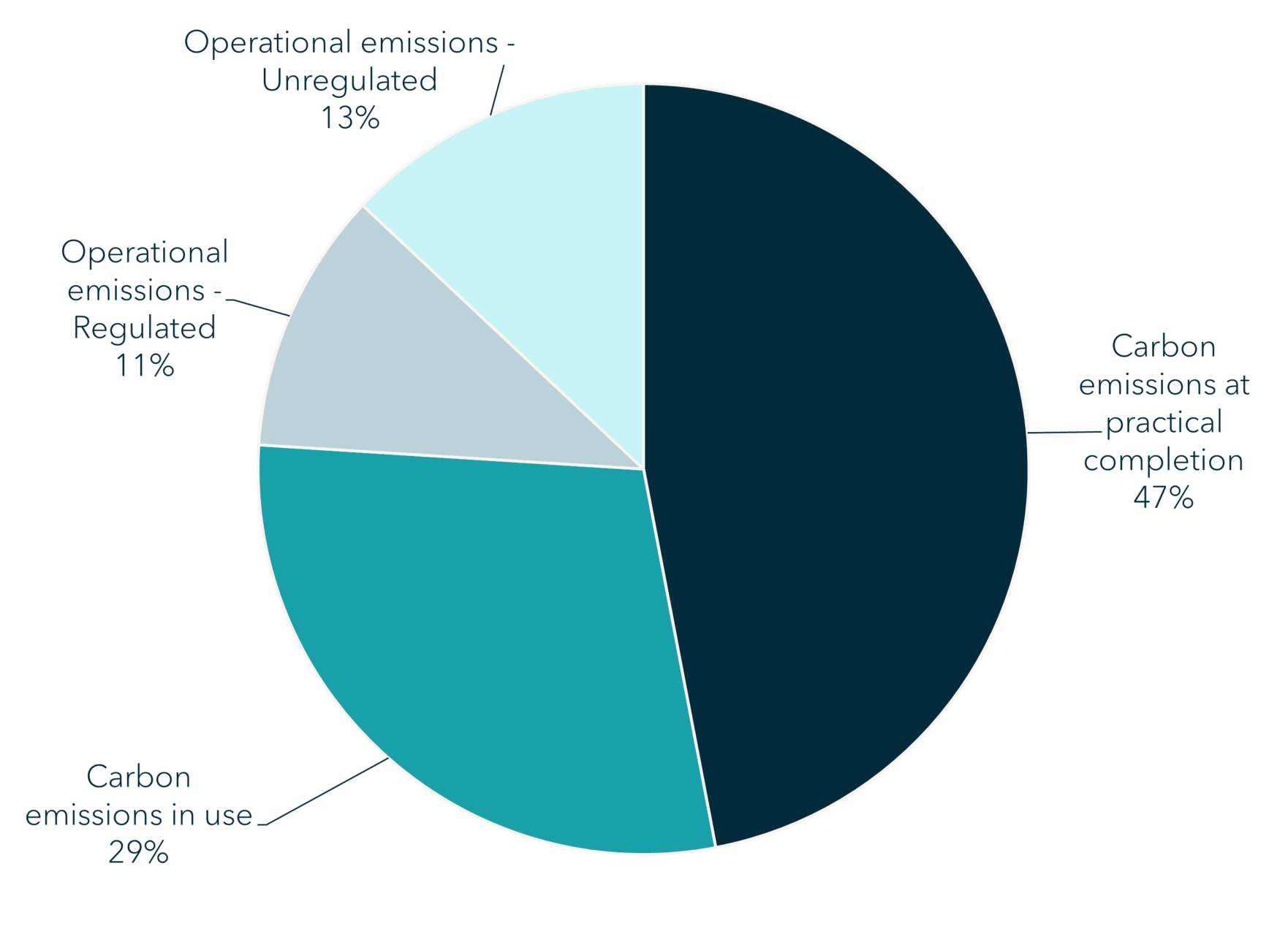

Historically, concentrating solely on operational carbon was the go-to approach, which often led to design choices that minimised operational emissions but inadvertently increased embodied emissions. Over the lifespan of a building, the embodied emissions at practical completion, along with those from maintenance and replacement, can constitute up to two-thirds of the total whole life carbon emissions, contingent upon the building’s typology as seen below.

Residential

Office

Industrial

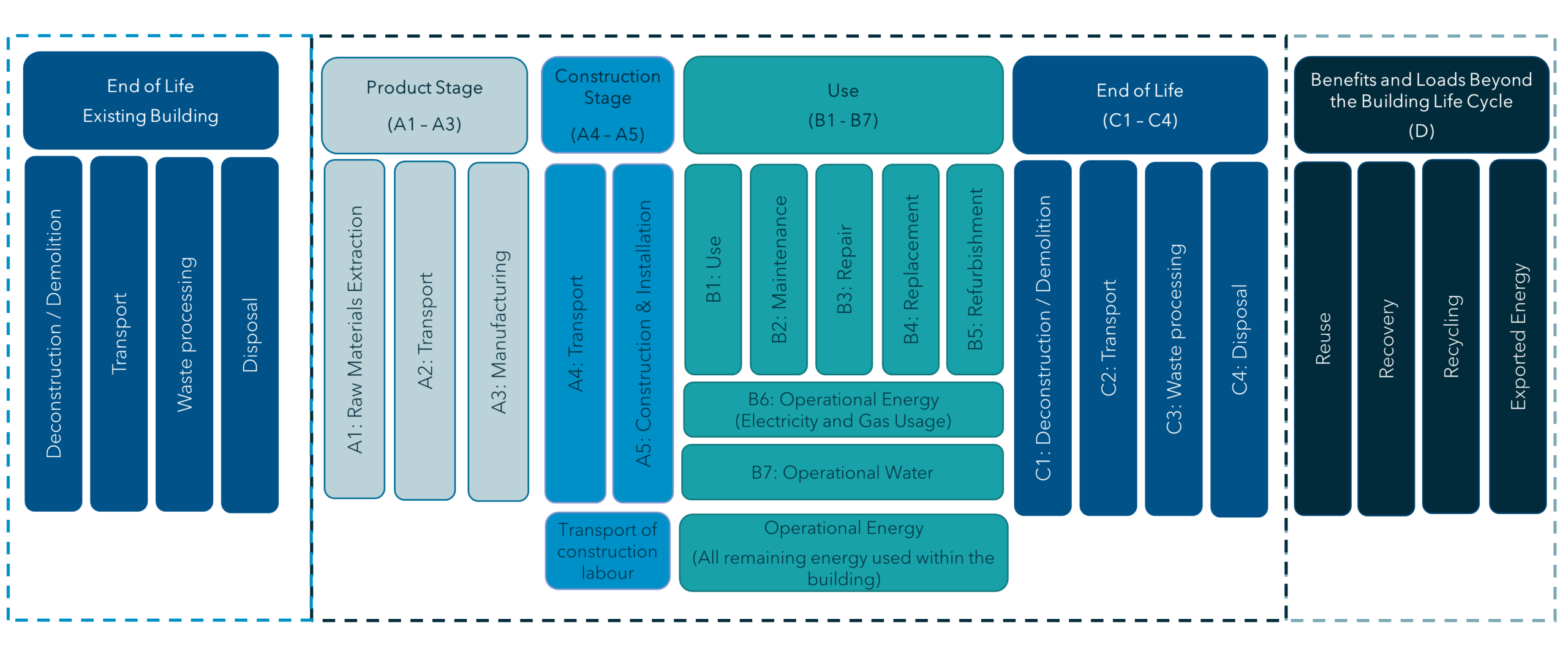

A whole life carbon assessment allows for more informed and accurate results. For projects requiring demolition and new construction, the emissions associated with demolition activities and the ‘end-of-life’ of the materials need to be included in the boundary of assessment as shown below. The upfront demolition emissions are often 10-15% of the total project emissions, based on our latest research.

New Construction Whole Life Carbon

Comparative Approach

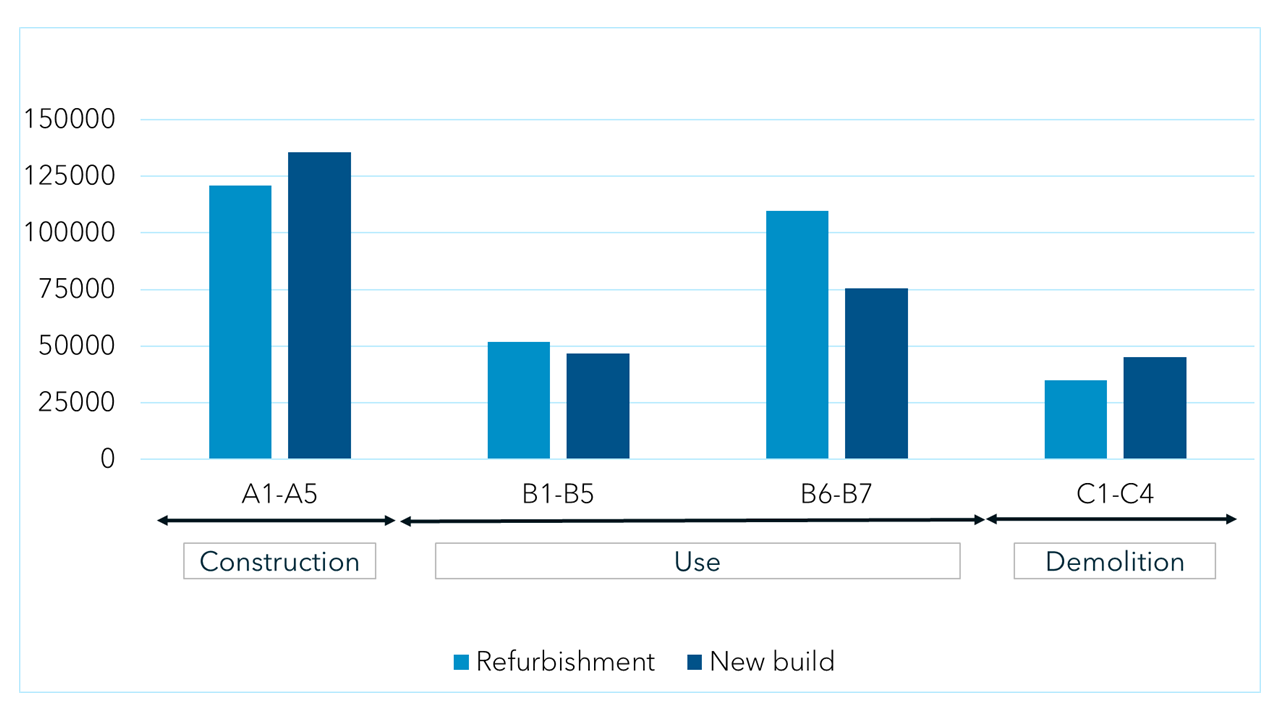

To give you an idea of what this comparative analysis looks like, here are two examples that delivered differing results:

1. Single-Family Dwelling – For a 200 m2 single-family dwelling in London, we conducted a comparative analysis between a deep retrofit and partial demolition and the construction of a new low energy building. In the refurbishment scenario, the front and rear brickwork facade, internal staircases, roof, and front door were retained, while everything else was replaced. In contrast, for the new construction, only the front facade was retained due to heritage preservation requirements, with the rest of the building being demolished and reconstructed. The results indicate that in terms of upfront embodied carbon (A1-A5), the refurbishment performs better. However, when considering the whole life carbon emissions of the building, the new construction option outperforms due to its superior energy performance. The new construction demonstrates an improvement of 85 KgCO2/m2 compared to the deep retrofit option.

Comparison Refurb vs. New Build

2. Abandoned Hotel – In a separate case, a comprehensive whole-life carbon comparison study was conducted for an abandoned hotel building in Bayswater conservation area, with gross internal area of approximately 2,700 m2. The refurbishment approach entailed the preservation of key components, including the façade, floors, and certain internal walls, alongside the installation of a new roof, windows, internal finishes, and necessary repair work on existing elements. In contrast, the new construction scenario included demolition of the existing structure and its replacement with a new building. The comparative analysis demonstrated that retaining the substructure and a majority of the superstructure in retrofit scenario described above resulted in a reduction of 278 kgCO2/m2.

Thinking Beyond Carbon

In any scenario you need to have a comprehensive understanding of the existing structures. A pre-redevelopment and pre-demolition audit is an exercise to understand the condition of the building before the decision to retrofit or demolish is made. If the whole life carbon assessment demonstrates that demolition and new construction is the preferred solution, then a pre demolition audit provides advice on the products and materials that can be reused, repurposed or recycled prior to any demolition.

Comparison Refurb vs. New Build

Based on a recent pre-demolition audit conducted by Eight Versa for a 1000 m2 single-family dwelling, 40% of the demolition-derived materials were successfully repurposed for the new project. Key strategies included utilising on-site superstructure and substructure concrete as sub–base fill and recycled aggregate (crushed on site to minimise transportation emissions). Additionally, bricks, roof tiles, and timber were reused on site. Through this conscientious material management approach and the selection of low embodied carbon materials for substructure, superstructure, and finishes, the project not only exceeded the extrapolated design targets for 2020-2030, along with the aspirational targets set by GLA but also achieved a performance rating surpassing A+ (LETI targets).

Futureproofing – The Role of Circular Economy

Circular economy thinking in new construction and retrofit plays an important role in futureproofing building assets. In a circular economy, products and materials are kept in closed loop circulation through maintenance, reuse, refurbishment, remanufacture, recycling, and composting. The circular economy tackles climate change and other global challenges by decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources.

Designing buildings that are adaptable, flexible and constructed using the principles of circular economy are easy to refurbish and retrofit in the future and will reduce the need to demolition and construct new buildings, thus reducing long term building emissions.

Balanced Evaluation

As you may have guessed, there is no one-size-fits-all answer between the rebuild vs. refurbish conundrum. Each scenario demands a thoughtful assessment, considering factors such as historical significance, budget constraints, sustainability goals, and long-term vision. The decision ultimately hinges on a balanced evaluation of the unique advantages and challenges of each development option, which can only be determined by conducting a comparative whole life carbon study. It is through this careful analysis that we can make informed choices that not only respect the past but also pave the way for a more sustainable and resilient future.

Authors

Rishika Shroff, Building Performance Manager

Rishika is a Building Performance Manager with an architectural background that enables her to work with design teams and create solutions that can enhance performance while maintaining coherence with their creative ideology.

Hesham Ahmad, Senior Sustainability and Building LCA Consultant

Hesham is a Senior Sustainability and Building LCA Consultant at Eight Versa. He has seven years of construction experience across a complex and diverse range of large-scale projects, including airports, tunnels, high-rise buildings and industrial factories around the globe.