Diminishing Returns

The technical consultation on the 2025 Future Homes and Buildings Standards published in December 2023, has been critiqued as being ‘a charter for business as usual’ (Architect’s Journal, Dec 23). This criticism arises from the fear that the standard will not result in fabric performance much higher than the existing Part L 2021 regulations. This may be justified assuming that the Future Homes Standard is supposed to act as the 7th Dan Black Belt in the art of energy efficiency. However, one could make a very strong case that U-values and fabric specifications have reached the point of diminishing returns and pushing them harder just results in higher embodied carbon and costs.

A New Mantra

For a long period of time, the ‘fabric first’ approach, which involves targeting a reduction in heating demand through a highly efficient fabric system, has been the uncontroversial stepping stone in the energy hierarchy. However, the rapid decarbonisation of the grid and emergence and deployment of technologies such as heat pumps, has led to critical discussions regarding the applicability of this mantra.

While one can argue that for new-builds, fabric should still come first, to ensure that demand is shrunk as far as possible to allow for peak demand management, micro-grid power sharing and climate resilience. However, when it comes to upgrading the existing building stock, it is not as straightforward.

A recent article published in Building and Cities, ‘Fabric first: is it still the right approach?’, the authors suggest that when considering the whole building stock, retrofitting fabric first might not be possible within the timeframe required for rapid decarbonisation, which in turn could slow down the decarbonisation of the housing sector itself. Studies find that the uptake rate of a ‘deep retrofit’ involving extensive measures is only 0.2% in the EU, where this approach is being actively promoted. This is predominantly due to lack of technical skills, supply chain issues and negligible demand given the high capital costs. On the flipside, the falling costs of renewables allow for low-carbon technologies replacing fossil-fuel at significant scale – this fundamentally changes the way we look at the overarching net-zero goal.

Case-by-Case

Our own experience on projects has found that there is no universal rule on where fabric enhancements should take priority over a services upgrade. While some cases have benefitted from a systems approach, where lighting, ventilation and heating technology upgrades have led to significant improvements in performance, on others we have found that for a heat pump to be efficient and appropriate for that project, fabric improvements are crucial. Therefore, a case-by-case approach is needed. However, as the Building and Cities article rightly suggests, at a building stock level, national ‘cost effectiveness’ should take priority while framing decarbonisation policy. In the medium term, zero carbon heating will be more important than fabric improvements to improve efficiency and reduce emissions.

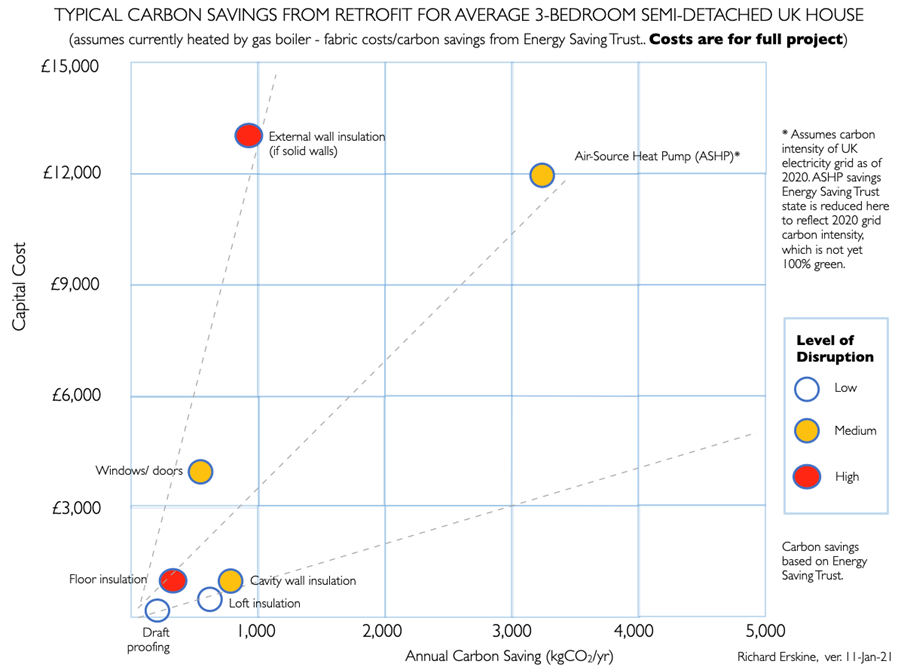

The authors also state that ‘to be cost effective, fabric should be improved up to the point where further improvement has a higher cost than future zero-carbon electricity supply, which will tend to exclude high-cost insulation. As indicated in the graph below created by Richard Erskine, the ratio of the annual carbon saving to the capital cost is a measure of cost effectiveness and in this case of an average semi-detached house, the option to choose is clear.

Moving Forward

Understandably, the answer to a stock wide decarbonisation strategy is not as simplistic as deciding on fabric first or not. We need multi-faceted policy approach which addresses the economic, technical and practical barriers which we encounter every week:

- Disproportionate capital costs for low-income households,

- More training of skilled workers,

- Increasing performance thresholds for technologies like heat pumps,

- Reducing the differential between gas and electricity prices,

- Minimum standards for existing buildings at key trigger points such as change of ownership.

The thing to remember is that times change. The world moves forward with technologies, economic models and innovations that disrupt standard operating procedure and long-held rules of thumb. This is nothing new; 15 years ago, LED lights were seen as a novel but somewhat expensive solution, 10 years ago combined heat and power units seemed like a sensible carbon saving strategy, 5 years ago few people considered embodied carbon as an important performance metric, and approximately 1 year ago ‘Fabric First, became ‘Fabric Sometimes’.

Rishika Shroff, Building Performance Manager

Rishika is a Building Performance Manager with an architectural background that enables her to work with design teams and create solutions that can enhance performance while maintaining coherence with their creative ideology.

If you’d like sustainability support with your building project. Feel free to book a meeting with one of our team to discuss further.