Technology has made a momentous contribution to human prosperity over the last two centuries. In one form or another, it underpins everything we do — to the point where we are concerned it’s going to take our jobs. However, it hasn’t always been this easy. It’s taken years of compounding development and innovation to get us to where we are today. It might not seem like it, as we are living in a time where rapid advancement in technology is a given, but it has come with many compromises.

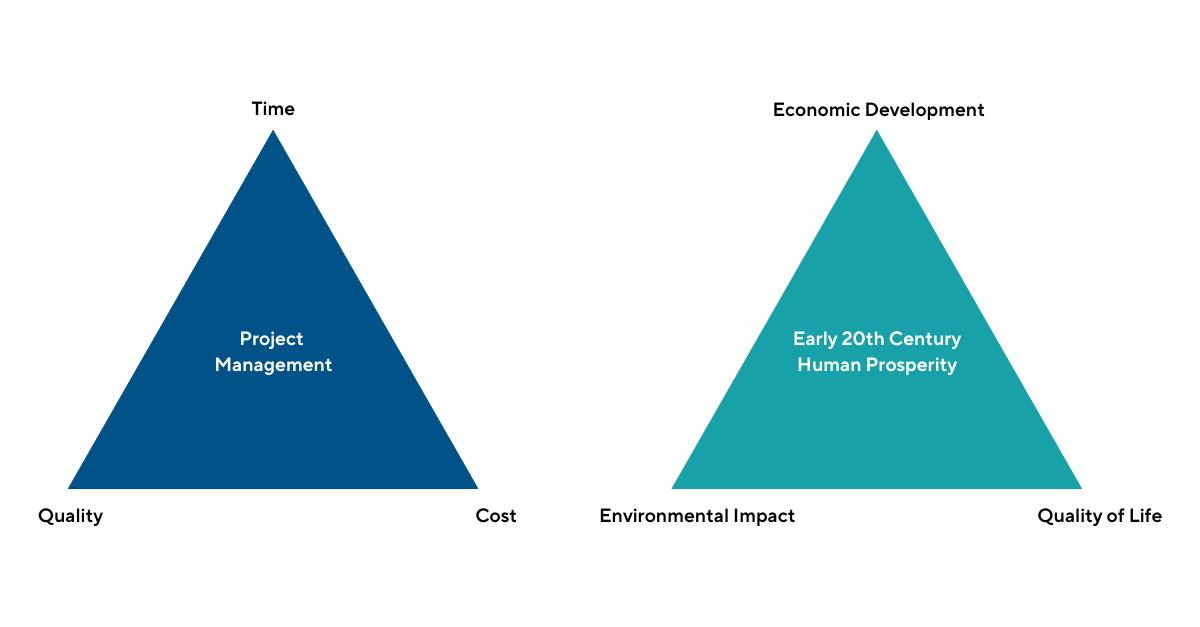

Triple Constraint

The triple constraint, also known as the trade-off triangle, is used in project management scenarios where there is often an interdependence and trade-off between three key elements: Scope, Time, and Cost. It is used to illustrate the idea that adjustments to one element will inevitably impact the other two. For example, increasing the quality of a project will inevitably increase the project timeline and costs, demonstrating that compromises will need to be managed.

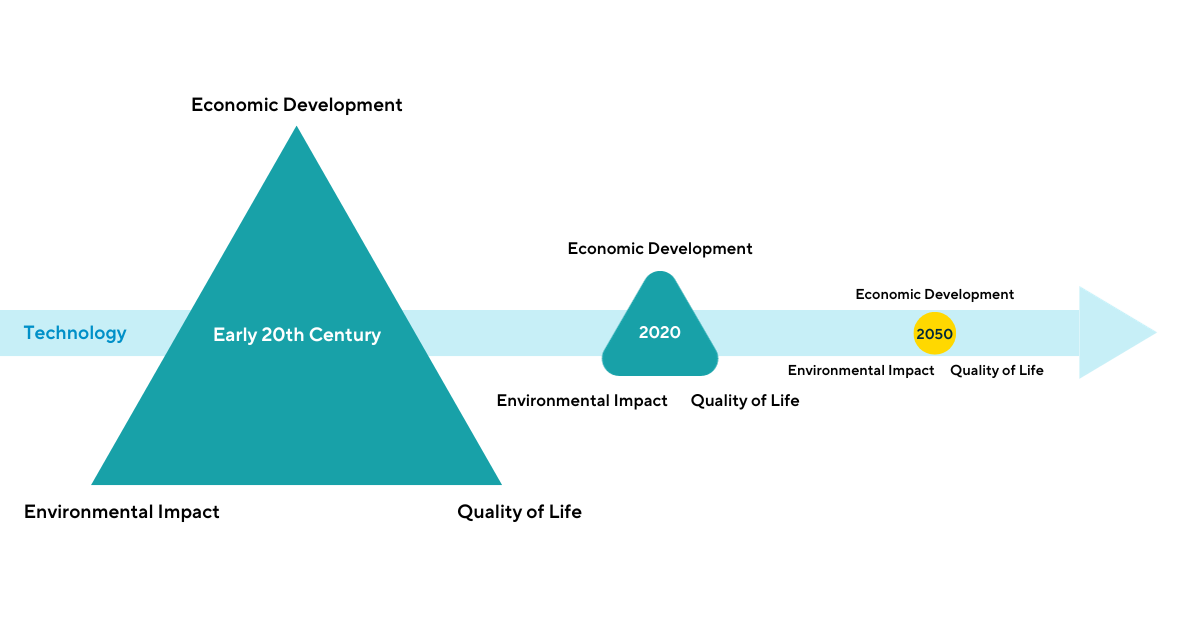

This model can also be applied to the role technology has played in human prosperity over time. The three key elements in this theorem are Economic Development, Quality of Life, and Environmental Impact, as shown below.

Reducing the Sacrifices

Historically, advancements in technology have always been centred around improving Economic prosperity and/or Quality of Life but balancing the inevitable trade-offs hasn’t been ideal. The industrial revolution of the 19th and 20th centuries unleashed unprecedented economic growth, which often came with a substantial negative impact on a lot of the population’s quality of life. If we evaluate the working conditions our great-grandparents and even our grandparents experienced, you’ll find that comparatively, we are living in a different world.

The fossil fuel-driven economic boom of the industrial revolution required millions of people to trade their lives and life expectancy. If you were a miner in Northern England, you were unlikely to reach your 40th birthday because of the working conditions you faced.

The third element in this triangle, Environmental Impact, has only recently become a consideration. Natural capital was a resource to be exploited like any other, and a place to deposit the by-products of Economic Development. The impacts of air and water pollution, along with the degradation of multiple natural habitats, has only recently been considered. 200 years on, the by-product of ever-improving economic conditions and quality of life is being felt in the form of climate change and natural degradation.

Given the extent of human knowledge and the physical composition of the natural world, this trade-off was mostly inevitable. However, it is only technology that can break this tri-trade-off relationship and establish a healthy and prosperous equilibrium.

Multiple Radical Leaps in Technology

The industrial revolution required people to sacrifice their lives to provide the first great leaps in technology. It is technically impossible to transition from a 16th-century agrarian society to one that can power itself on renewable technology. Our current paradigm demanded the proliferation of information and the cultural opening of the Renaissance, followed by the unprecedented explosion in available energy derived from millions of years of solar energy and decomposing life in the form of fossil fuels. This was followed by the advanced industrial age, during which computing and science allowed us to deconstruct the world around us to find ever more solutions to our problems.

It would be technically impossible for the modern world we have today to exist without the mass proliferation of fossil fuels for two centuries.

Technological advancement can be visualised as a ladder, with each rung providing an achievable and conceivable next step. The next rung of renewable technologies and biogenic materials relies on the foundation provided by the previous rungs of energy-dense fossil fuels to create them. Now that we stand on the fossil fuel rung, we have the opportunity to utilise our resources to ascend to the next rung without imposing such significant sacrifices on human health and wellbeing.

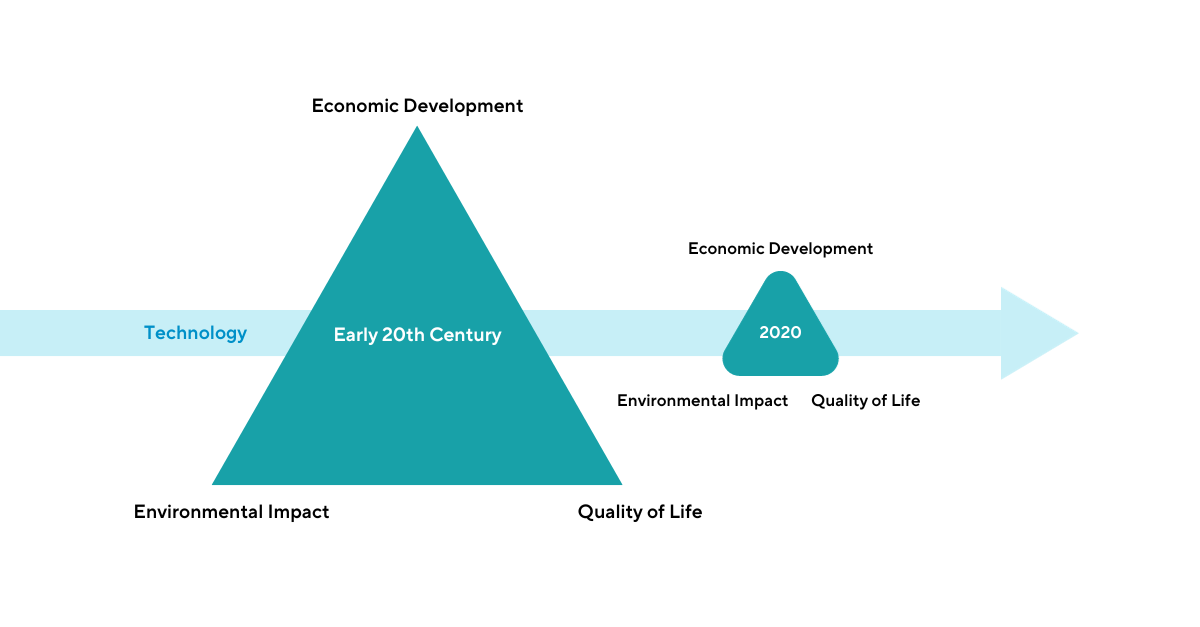

The last three to four decades have witnessed the acceleration of technology with the potential to reduce the severity of these trade-offs. The past 20 years have marked the most significant improvement in the quality of life in human history. Contrary to common belief, this has been increasingly achieved with a lower Environmental Impact per person. The factors driving the unsustainability of our current paradigm are the intensity of activity, along with its sheer scale. The image below contrasts our current triple constraint with life 100 years ago. The point being that the trade-offs are less severe; we can extract more outputs with higher utility, and we are all experiencing a better quality of life with less Environmental Impact.

However, to significantly reduce the Environmental Impact trade-offs, we still require multiple radical leaps in technology. The concept of decoupling Environmental Impacts from our prosperity has been part of the sustainability conversation for decades. However, since it demands substantial advancements in technology and solutions, we have recently seen suggestions of ‘degrowth’ or even a ‘well-being economy.’

Neither of these options is technically, culturally, or practically viable, and establishing a culture and system based on these principles would take generations. Thus, we are left with one practical option: to innovate our way out of the triple constraint paradigm. The scale of the transformation needed is nothing short of monumental, encompassing radical advancements in energy storage, materials science, carbon capture, alternative fuels, agriculture, and beyond.

Creating an Uncompromising Circle

Regrettably, at this point in time, significant trade-offs still persist within our technological paradigm. Depleting natural capital and emitting CO2 emissions are intrinsically connected to most modern human activities. Therefore, this impact must demonstrably contribute to progress on the next rung of the development ladder.

Our current capital and fossil fuel resources must be directed toward radical innovation and extensive research and development (R&D) programmes. This solution is often overlooked in decarbonisation efforts. However, it is the only realistic pathway to achieve a low-carbon future.

Failure to harness the resources at hand to foster the development of the next generation of technologies over the next two decades will result in us remaining locked-in to a low prosperity, climate-imposed degrowth paradigm. This would leave us without the necessary resources and environmental capacity required to ascend to the next rung of the ladder.

The primary goal is to create technology that transforms the triple constraint triangle into a small circle where, actions in one direction yield only marginal trade-offs in another, as illustrated below.

Hindering Progress

Organisations of all kinds require the freedom to innovate and grow. However, with current Net Zero frameworks like SBTi, companies are discouraged from doing so. To achieve Net Zero, companies are mandated to achieve a 90% absolute reduction no later than 2050, according to the SBTi methodology. What this fails to acknowledge is that companies that provide the necessary innovations for decarbonisation cannot align with such a framework.

For instance, Tesla’s meteoric growth and its potential to impact climate change significantly are noteworthy. However, under the SBTi methodology, Tesla’s carbon roadmap would not be deemed suitable, and therefore, it couldn’t attain Net Zero status. Few sustainability experts envision a sustainable future without electric vehicles. Yet, how were electric vehicles expected to be developed? It took Tesla a decade of R&D and a substantial carbon footprint to create a commercially viable product and, crucially, to disrupt a market dominated by indifferent and EV-sceptical incumbents.

One could argue that Tesla is more committed to addressing climate change than any other car manufacturer; it’s products allowed customers to avoid 13.4 million metric tonnes of emissions in 2022 alone, which is roughly the same as Lithuania’s total emission output in 2021. Yet, Tesla’s emissions increase each year.

Consequently, frameworks such as SBTi do not truly recognise Telsa and hundreds of companies like it as a desirable contributor to the Net Zero objective. We need to reconsider what progress truly entails. If we are genuinely committed to achieving Net Zero across all sectors, we must adopt a more realistic perspective of what this means in reality. It will resemble the urgency and focus applied to finding a Covid-19 vaccine or even the industrial mobilisation necessary to win World War II.

Intensity Matters

Consequently, we advocate pursuing decarbonisation based on output intensity; 1 tonne of carbon per unit sold, or £1000 of turnover, not carbon budgets. To encourage and facilitate innovation and R&D in all sectors, including within organisations, we need a methodology that is accessible, flexible, and inclusive, especially for SMEs. The companies of tomorrow need to participate in reducing their emissions, but they must design and build the innovative products and services that contribute to creating a low-carbon economy.

A dogmatic adherence to carbon budgets (or ‘Absolute Contraction’ as termed by SBTi) will not work. We need to remember that merely existing creates an environmental footprint. Testing ideas and building new solutions also creates a footprint.

Organisations will soon discover for themselves that they cannot expand revenue and market share while simultaneously reducing their emissions. This will lead to disillusionment in the Net Zero mission. Instead, we should look to evaluate the utility of an organisation’s actions in creating their footprint. Is your impact a justified expense in making the world a better place? Are you actively contributing to your sector, and perhaps to all of us taking the next step on the ladder?

If the answer is a sincere ‘yes’, then you are on the right track.

How SBTi is Not for the Little Guy Whitepaper

Net Zero and setting a decarbonisation pathway is a complex subject that can’t be summarised in 1500 words, and so we have created a more extensive argument for an alternative approach to decarbonising in our latest whitepaper here. If you are interested in finding out more about setting realistic carbon reduction targets you can get in touch with one of our experts who would be happy to help.