Lay of the Land

Net Zero is the desired target. However, the route to get there is still in contention. Many businesses have now understood the importance of CO2 mitigation and begun to navigate the complexities of reducing their emissions. But when considering the long-term pathway to Net Zero it’s not clear what is realistic or even possible.

It’s widely understood that the initial priority is to reduce Scopes 1, 2 and subsequently Scope 3 emissions by as much as possible. This can be achieved by investing in energy-efficient technologies, switching to renewable energy sources, and making changes in the supply chain processes. This approach aligns with the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), which calls for companies to set ambitious emission reduction targets and achieve annual minimum carbon reductions.

However, achieving these annual reduction targets is very challenging and often expensive, particularly for companies in energy-intensive sectors or those with complex global supply chains. It is estimated that for the UK this could cost between £12 – 79 billion per year, and £1 trillion by 2050 (the entire UK defence budget is £46 billion per annum). Many Net Zero estimates also do not adequately include debt financing costs, which if added would mean billions of pounds of debt interest per annum and add 20% onto the debt to GDP ratio.

Moreover, many of the technologies needed to achieve deep decarbonisation, such as green hydrogen, advanced batteries, carbon capture and storage, biogenic and non-fossil fuel based materials are still in the initial stages of development and may not be commercially viable for decades, which imposes a practical limit on the potential for decarbonisation. This is where offsetting comes in.

Conventional Wisdom

There are 2 main types of offsetting options for businesses to consider. Each of these options are sold as credits which are quantified by the estimated emissions that they either avoid or remove:

- Avoidance – this refers to the measures taken to prevent the release of CO2. For example, renewable energy projects or avoided deforestation.

- Removal – this involves activities aimed at removing CO2 and storing it in long-term reservoirs. For example, afforestation, reforestation or engineered removals such as Direct Air Capture.

Carbon avoidance credits have faced criticism and controversy in recent years, partly due to concerns about their integrity and real impact. In some cases, projects that claim to reduce deforestation or protect natural habitats have been accused of exaggerating their benefits, displacing local communities, or creating perverse incentives for unsustainable land use practices. For example, a 2019 investigation by ProPublica found that many forest carbon offset projects in Brazil were overestimating their impact on reducing deforestation, while failing to address the underlying drivers of land use change, such as poverty, corruption, and weak governance. In 2023 an investigation by Guardian, Die Zeit and SourceMaterial, stated that more than 90% of their rainforest offset credits are likely to be “phantom credits” and do not represent genuine carbon reductions. These criticisms pivot around questionable additionality (i.e., whether they would have happened anyway without the carbon credit revenue) and permanence (i.e., whether the carbon savings will be reversed in the future due to natural or human disturbances).

Removal credits are often considered preferable to avoidance, but they tend to cost more. Until the formal definition of Net Zero in 2021 and the subsequent requirement focus on internal reductions only, carbon credits were considered a viable means of decarbonisation. Many environmental activists and NGOs now argue that relying on carbon avoidance credits or other offsets can be a distraction from the urgent need for companies to reduce their own emissions and transform their business models. In the face of the difficulty in reducing emissions some have even called for a “degrowth” approach, arguing that companies should prioritise reducing their overall consumption and production levels, rather than trying to offset their emissions through external projects. While that might work on paper, it is a ludicrous model that would not work in real life – at least not anytime soon.

Despite these criticisms, there is recognition that purchasing carbon avoidance credits or investing in nature-based solutions is a necessary part of reaching Net Zero. Protecting and restoring natural ecosystems can be a powerful tool for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Carbon avoidance credits aim to protect existing forests, wetlands, and other ecosystems that act as natural carbon sinks. According to a 2021 report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), nature-based solutions could provide up to one-third of the climate mitigation needed to achieve the Paris Agreement goals by 2030, while also supporting biodiversity, ecosystem services, and sustainable livelihoods – helping a business also achieve their UN Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs). According to a 2020 report by the World Economic Forum, the global market for nature-based solutions could create 191 million jobs and generate $10.1 trillion in economic value.

UN SDGs

Moreover, these solutions can be highly cost-effective: a 2021 study by the World Resources Institute estimated that every dollar invested in nature-based solutions could generate up to $7 in economic benefits, such as increased crop yields, improved water quality, and reduced disaster risk. Some companies have made carbon avoidance credits and other nature-based solutions a core part of their climate strategy. For example, in 2021, Gucci launched a “Natural Climate Solutions Portfolio” that aims to protect and restore critical ecosystems and biodiversity. Similarly, in 2021, Shell announced a new “Nature-Based Solutions” business unit that aims to invest $100 million per year in projects that protect, transform, or restore natural ecosystems, such as forests, wetlands, and grasslands. Shell is aiming to use nature-based solutions to offset 120 million tonnes of CO2 emissions per year by 2030. While some environmental groups have criticised Shell’s approach as greenwashing its fossil fuel operations, one could argue that until we break the planet’s utter dependence on fossil fuels then traditional energy companies recognising the value of natural capital and ecosystem services is an interim step forward.

The Way Forward

Carbon avoidance credits and removal credits from nature-based solutions can play an important role in the climate mitigation toolkit for companies. Unfortunately, there have been numerous examples of credits being used to launder company images and as a PR tool to cover up third rate climate action. However, we must not throw the baby out with the bathwater.

The most effective and efficient CO2 mitigation strategies depend on the specific circumstances and capabilities of each company, as well as the broader regulatory framework and market context in which they operate. The conventional wisdom of internal reductions first is broadly a sound principle. However, there is a fundamental principle and iron law of productivity which is often overlooked by poorly informed sustainability advocates. All productive action experiences the law of diminishing returns, whereby each subsequent action becomes more costly for the same benefit.

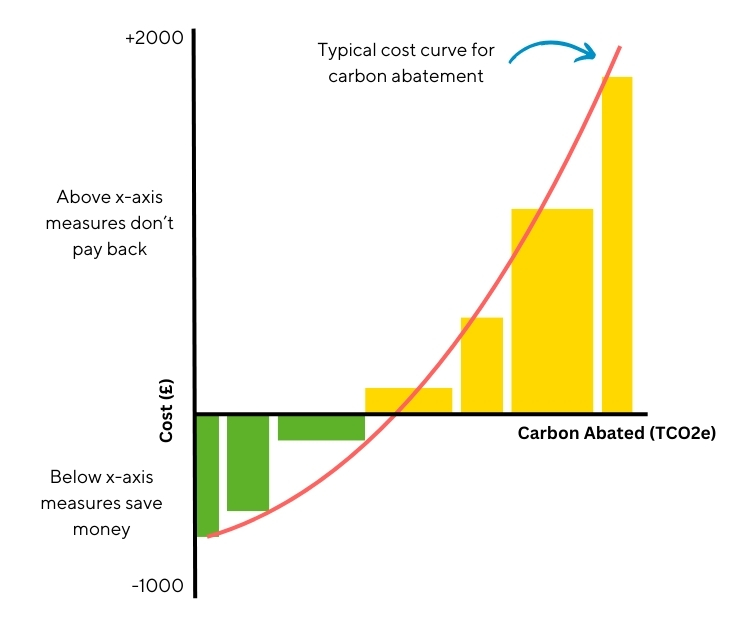

This is best demonstrated via a Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MACC) which is used to help organisations identify and prioritise emission reduction opportunities based on their relative costs and benefits.

Abatement Cost Curve

MACC showing the non-linear relationship

between the cost and a tonne CO2 saved

Every organisation experiences this phenomenon. Therefore, the pragmatic approach would be to focus first on internal reduction measures that are cost-effective and technically feasible. Once the cost of internal reductions exceeds a certain threshold, i.e. where the £ spent per tonne of CO2 saved (including accruing cost savings) exceeds the cost of sponsoring a conservation project then, then the organisation should switch to protecting and enhancing natural carbon sinks. Finally, the scaling up of carbon removal solutions should be sponsored as they become more mature and affordable.

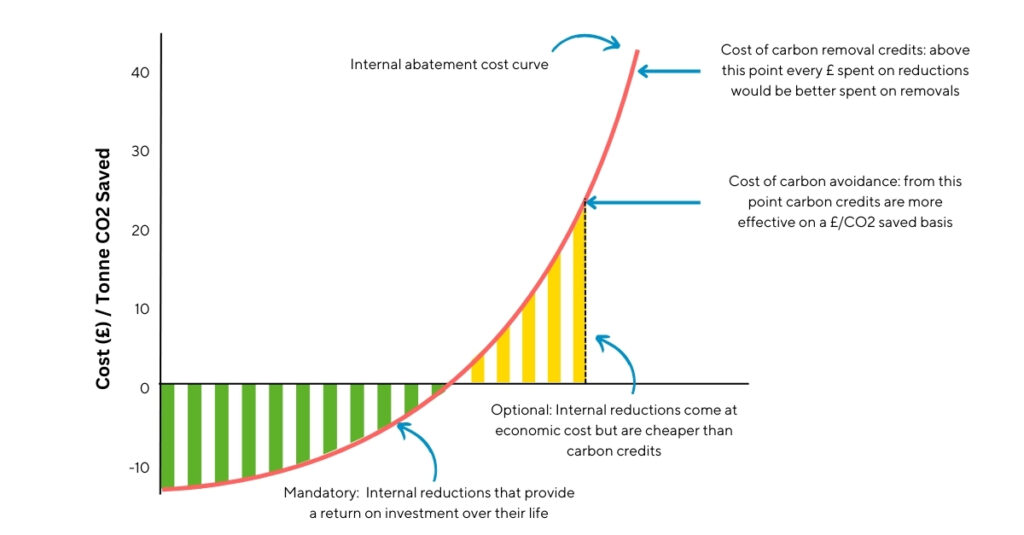

This approach is shown diagrammatically below.

Carbon Saving Measures

Diagram illustrating the prioritisation of carbon saving measures and how credits

can be significantly more cost effective than internal reduction after a certain point.

Invest Intelligently

Carbon avoidance credits are often seen as inferior to carbon removal credits. However, this is a perverse perspective as replacing a natural carbon sink is much more costly and environmentally impactful than just protecting it from degradation in the first instance. For this mindset of conventional wisdom to switch, there will need to be significant improvements in the quality, transparency, and accountability of carbon avoidance markets and credits. The cynicism towards carbon removal credits is justified because of previous scandals, and removals credits like planting trees are more intuitively rewarding, i.e. there wasn’t a tree there previously but there is now, so the additionality is clear.

Contrary to rigid carbon reduction standards like SBTi, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to prioritising CO2 mitigation strategies, a nuanced and evidence-based approach is needed that considers the costs, benefits, and trade-offs of each option is required so organisations can maximise their climate change mitigation with the financial and resource constraints that all organisations are subject to.

If organisations invest intelligently in a more diverse portfolio of solutions, including internal emissions reductions, carbon avoidance credits, and nature-based or technological solutions, then they deliver more climate impacts than they would by just pushing a one-dimensional approach. And crucially, they can also contribute to safeguarding and building a more resilient and ecosystem rich world, that is worth going against conventional wisdom for.

Chris Hocknell, Director

Chris brings over 18 years’ experience of supporting the built environment and corporate world with their sustainability goals. Specialising in sustainability strategy development, Chris works closely with clients to assess and understand their carbon and environmental footprint.